Space: the new economic frontier

Innovation. Exploration. Opportunity. It’s time for entrepreneurs to boldly go where no startup has gone before, says Dr René Olie.

On 1 February 2003, Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated as it returned to Earth, killing all seven astronauts on board. The subsequent investigation found that the shuttles were old and unsafe — and the following year, NASA announced the cancellation of its $196bn shuttle program. Clearly, a new way of doing things was needed — especially as the US was now reliant on other nations, such as Russia, to deliver crew and cargo to the International Space Station (ISS).

And so, on January 18, 2006, NASA launched the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) model. “It kicked off a new era of commercial space exploration, inviting private companies to come up with ideas for new spacecraft,” says Dr René Olie, Associate Professor of Strategic and International Management, and Director of RSM’s Space for Business program. Costing a relatively low $800m, the scheme proved revolutionary. “One of those companies was Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which developed the first-in-class reusable Falcon 9 rocket — the most successful commercial rocket ever built,” Olie points out. “And now, space is the new economic frontier.”

Prior to COTS, the space industry was traditional and institutional, and governments were the key players. “The country’s space agency was compensated for all their costs, plus a profit margin, which as any economist can tell you, is a brake on innovation, as there’s no urgency to save money by doing things differently,” says Olie. “In contrast, the COTS program incentivized companies to develop ideas quickly and produce them cheaply. Increasingly, space agencies started handing out all kinds of requests for products and services to space companies. This proved to be much faster and more cost-efficient than the traditional model.”

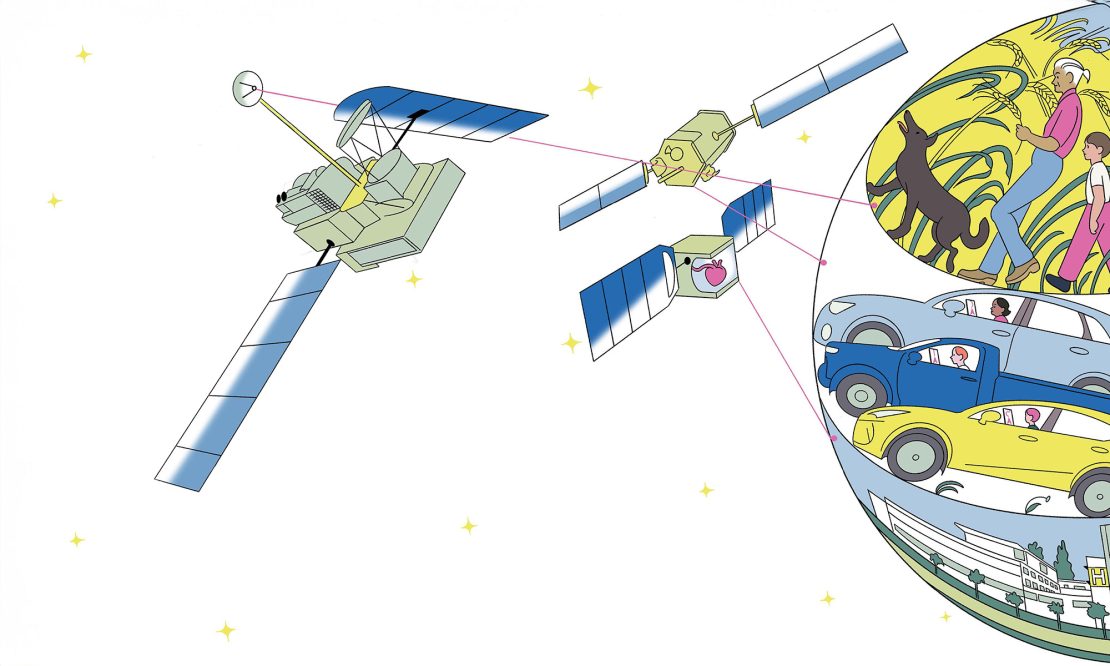

In fact, a recent report from McKinsey predicts that the global space economy will be worth $1.8trn by 2035 (accounting for inflation) — a huge rise from $630bn in 2023. That figure includes ‘backbone’ applications — such as those for services like broadcast TV — and ‘reach’ applications, where space tech helps companies generate revenue, such as the satellite signals in smartphones that Google Maps relies on. “SpaceX has shattered the illusion that everything to do with space has to move at a glacial pace and be hugely expensive,” says Olie.

RSM is well placed to take advantage of these new opportunities: it has now been working with the European Space Agency (ESA) and its incubator at Noordwijk for 20 years. Students undertake a range of projects, from developing commercial applications with a business plan to consultancy assignments looking at issues within the ESA. It’s a win for both parties, says Olie. “These programs demystify this high-tech sector for business students. And the space sector still tends to be inward-looking, with very strong engineering skills but very limited commercial skills. We want to cater to the needs of people already working in the space sector as well as those who might want to move into it, as it becomes increasingly commercialized.”

Space technology, after all, is part of our lives. It was NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, for example, that invented the CMOS sensor — now a ubiquitous part of your smartphone’s camera — and satellite data is everywhere from weather apps to Google Maps. Many of the startups Olie works with focus on ideas using satellite data, such as a tracker for football players used across the world, enabling them to monitor their performance on the field. Precision agriculture, where satellites monitor rainfall, soil condition or methane emissions, is another key area around which business models could be developed, as is tracking CO2 emissions.

Of course, working in space brings extraordinary challenges. But Olie believes that opening up the industry will help make it more normalized and less exceptional, attracting bright minds who previously might not have seen themselves as space-age entrepreneurs. The ISS, he points out, will be phased out towards the end of the decade. “Now, commercial companies have all kinds of plans to develop new, commercial space stations. For example, I know of one Swiss-based company that plans to grow organs for transplantation in space: the microgravity means you can do it much faster. Imagine needing an organ, sending off your stem cells, and then having them grow one for you very quickly — that’s much better than waiting for someone to donate one!”

And the field is now wide open for savvy entrepreneurs from business backgrounds, says Olie — proving that the business of space isn’t necessarily rocket science. “Elon Musk is a great example: he’s breaking up the satellite company monopoly with Starlink. Aside from the potential satellite data, we could see opportunities around mining rare minerals or gaining geopolitical advantage — India and China have now landed on the moon. This new economic frontier is sparking competition, innovation — and opportunity.”

Interested in the Space for Business programme? Find out more here